The skulls of animals shot in the forests around Bratislava line the wall behind Marek’s head. His mum brings deer, duck, dumplings, and sauerkraut to the table outside, as well as juice made from stinging nettles and fruit. She continues to put food on the table until there is no space left. After we plow through the delicious main course, it’s time for poppy-seed cakes and coffee.

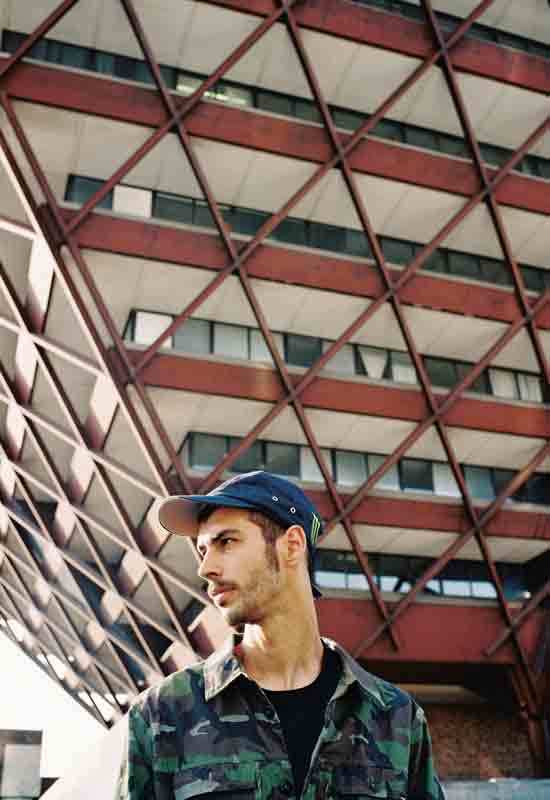

On our drive back to the apartment, we discuss the places Marek and Kubo grew up skating and shooting photos at: Slavín, Istropolis or Dom Odborov, the UFO hovering over Most SNP, Petržalka, and the Slovak Radio Building. It becomes clear that finding interesting examples of Bratislava’s Soviet architecture isn’t going to be difficult. Though, whether these spots are fine to skate decades on from their original construction remains to be seen.

Finding yourself alone in London, Paris, or Berlin, you’d probably have a good idea of where to head in search of friends: Southbank, République, or Warschauer Straße. Now repeat this little exercise for Zagreb, Tbilisi, or Bratislava.

If potential meet-up spots for these three cities don’t come to mind readily, I wouldn’t be too surprised. Coverage of skateboarding in the countries formerly associated with the USSR and socialism (rebranded in recent years under the vexed term “New East”) is scant though there are, of course, some fine examples.

Even politicians have trouble with the New East’s geography. George W. Bush made a fool of himself telling a Slovak journalist that “the only thing I know about Slovakia is what I learned firsthand from your foreign minister, who came to Texas.” He had, in fact, met the Prime Minister of Slovenia.

"You who enter here, take away your pain and sorrow, we died for you"

In April, we set off in the first of the two countries confused by Bush; the one that borders the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland, Ukraine, and Hungary, and that until 1993 was a part of Czechoslovakia.

Bratislava, Dukla, Prešov, Košice, Liptovský Mikuláš, Zvolen, Banská Bystrica, Lučenec, Komárno, Nitra, Žilina. The names of the Slovakian towns and cities conquered in battle by the Soviet Army are glorified in marble relief on the sides of Bratislava’s Slavín memorial, along with the dates of the victories.

“You who enter here, take away your pain and sorrow, we died for you,” goes a rough translation of the bronze text that frames the door to the memorial. Atop the central pillar stands a Soviet soldier, hoisting a flag up whilst stamping on a swastika.

To the right of the large four block, there is a statue depicting a Soviet soldier working together with a Slovak boy to prop up a wounded man. The friendship between the conqueror and the local is a dominant motif in Soviet memorial architecture and is especially prevalent in the monuments of Central Asia, where local elders are portrayed giving their consent to the Soviet soldiers heading off to fight in Europe or Afghanistan. These monuments offered a model for the relationship between the locals and the Soviets and attempted to foster a sense of togetherness across what was a vast and heterogeneous union.

From the vantage point of the memorial high above the city, the viewer looks down upon the urban sprawl. What becomes clear is the way in which the various districts are parceled together. There’s the red-brown roofs of the houses next to the hrad, or castle, where the city’s richest residents live. And then there’s Petržalka further out, after the UFO, where a lot of people were relocated by the Soviets.

The painted second floor panels of Petržalka’s housing blocks date back to the ‘70s and ‘80s when architects began to experiment with using different colors in their designs. In towns and villages, color was often used to gesture towards the landscape (forests, meadows, sand) surrounding the blocks. Murals were also added in an attempt to brighten up the districts. To this day, locals use the nickname paneláky for the blocks, referring to the pre-fabricated panels used in the construction of the Petržalka district.

Thursday is the first rainy day of our seven-day trip, so we drive to Devín Castle, where the rivers Morava and Dunaj meet. The confluence is marked by an abrupt change in the water’s color from brown to blue, along an almost perfect straight line. Starting out as the Donau in Germany’s Black Forest, the river runs through Slovakia as the Dunaj, and after completing a journey of 2,850 km [1770 miles, editor’s note], ends up in the Black Sea.

The castle is surrounded by green hills and forest. In the small lake, there are croaking frogs, and in the river, there may be a few last Danube salmons, which are now found mostly in Slovenia and Montenegro. The real tragedy of the river is marked by a monument on its bank.

Aranož V, Babič F, Bačik L, Bakoš R, the list runs on. The names of the Czechoslovakians who wished to escape over the river into Austria and the West are engraved into the Gate of Freedom. The bullets that pockmark the columns would have also been fired into the river, at the civilians trying to swim against the strong current to safety. These would have been desperate last moments.

The monuments are here to remind us of this desperation and horror. Though it’s not quite as straightforward as this. Whilst researching this article and the accompanying edit, it became clear that many of the sites we planned to skate are mired in live debates about the ways in which we respond to Soviet architecture. The erasure of Soviet monuments in Poland, “ruin porn”, and the online presentation of former Yugoslavia’s Spomeniks (Serbo-Croatian for “monuments”) as “concrete clickbait” are just a few examples of such debates.

We were mindful of the ways in which this sort of content is often framed as venturing into some new or unexplored territory – of course, there’s nothing new about these spots, they’ve been here all along. The grass is pushing up through the floor at Istropolis, and the ledge at the Slovak Radio building is black with wax.

Though new infrastructure is being built throughout the city, nothing looks as distinctive as the architecture from the Soviet era or has such a rich historical context.

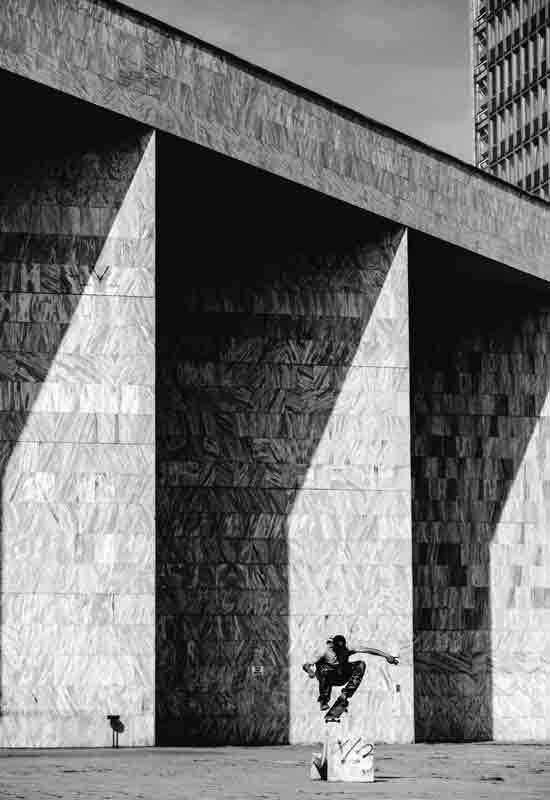

Switch Frontsideflip

The castle is surrounded by green hills and forest. In the small lake, there are croaking frogs, and in the river, there may be a few last Danube salmons, which are now found mostly in Slovenia and Montenegro. The real tragedy of the river is marked by a monument on its bank.

Aranož V, Babič F, Bačik L, Bakoš R, the list runs on. The names of the Czechoslovakians who wished to escape over the river into Austria and the West are engraved into the Gate of Freedom. The bullets that pockmark the columns would have also been fired into the river, at the civilians trying to swim against the strong current to safety. These would have been desperate last moments.

The monuments are here to remind us of this desperation and horror. Though it’s not quite as straightforward as this. Whilst researching this article and the accompanying edit, it became clear that many of the sites we planned to skate are mired in live debates about the ways in which we respond to Soviet architecture. The erasure of Soviet monuments in Poland, “ruin porn”, and the online presentation of former Yugoslavia’s Spomeniks (Serbo-Croatian for “monuments”) as “concrete clickbait” are just a few examples of such debates.

We were mindful of the ways in which this sort of content is often framed as venturing into some new or unexplored territory – of course, there’s nothing new about these spots, they’ve been here all along. The grass is pushing up through the floor at Istropolis, and the ledge at the Slovak Radio building is black with wax.

Though new infrastructure is being built throughout the city, nothing looks as distinctive as the architecture from the Soviet era or has such a rich historical context.

Nollie Frontside Bigspin

Aranož V, Babič F, Bačik L, Bakoš R, the list runs on. The names of the Czechoslovakians who wished to escape over the river into Austria and the West are engraved into the Gate of Freedom. The bullets that pockmark the columns would have also been fired into the river, at the civilians trying to swim against the strong current to safety. These would have been desperate last moments.

The monuments are here to remind us of this desperation and horror. Though it’s not quite as straightforward as this. Whilst researching this article and the accompanying edit, it became clear that many of the sites we planned to skate are mired in live debates about the ways in which we respond to Soviet architecture. The erasure of Soviet monuments in Poland, “ruin porn”, and the online presentation of former Yugoslavia’s Spomeniks (Serbo-Croatian for “monuments”) as “concrete clickbait” are just a few examples of such debates.

We were mindful of the ways in which this sort of content is often framed as venturing into some new or unexplored territory – of course, there’s nothing new about these spots, they’ve been here all along. The grass is pushing up through the floor at Istropolis, and the ledge at the Slovak Radio building is black with wax.

Though new infrastructure is being built throughout the city, nothing looks as distinctive as the architecture from the Soviet era or has such a rich historical context.